Drive-Thru Pedagogy Blog

Pick up something practical.

The Power of a Good Story

November 22, 2021 • Laurie Koloski

Many of us rightly emphasize “critical reading” in our courses, helping students hone the tools they need to unpack and evaluate the storylines they encounter, whether in historical or contemporary texts, written or visual sources, scientists’ data or politicians’ campaigns. It’s also important, though, to get students thinking about what’s involved in producing the best possible stories, and this is something I’ve begun devoting more attention to in the COLL 100 course I regularly teach, “Things: Objects and Their (Hi)Stories.” The better a storyline, the greater an author’s chances of getting what s/he’s after, but it’s important to be clear about what we are—or should be—aiming for when we attempt to produce a good story.

In earlier iterations of this course, I assigned a multi-step narrative timeline project (using Timeline JS) titled “One Object, Three Moments, Three Meanings,” which emphasized how a single object’s meanings and uses can change over time. Shifts in meaning over time are one of historians’ key concerns, but many objects carry multiple meanings even in a single historical moment, and these are difficult to highlight in a timeline’s linear format. In addition, students had to devote so much energy to uncovering an object’s complex and changing history that they had little time to think about which aspects of their object were most interesting to them and why.

In part because of these challenges and in part because of the pandemic, which led me to incorporate online museum sites into the course, I’ve shifted to a new multi-stage project called the “Object Project,” which includes four components:

- Analyzing an object’s museum story:

Students begin by identifying an interesting object that’s part of a museum exhibit and unpacking the storyline that curators have presented. From the very beginning of the project, then, they’re thinking critically about who is telling an object’s story and how and why they’ve done so. - Exploring “beyond-museum” stories:

Drawing on course texts from earlier in the semester, students “read” the object’s construction, materials, and other clues to brainstorm alternative stories they might be able to tell. What might the fabric of an unholstered chair, for example, tell us about social, economic, and political systems as well as material objects and processes? How might the people who sewed an astronaut’s space suit reveal something that the suit’s user could not? - Investigating a new story:

From here, students use University Libraries’ resources to research a beyond-museum story that they find most interesting, either delving more deeply into a particular aspect of their museum object or exploring a broader contextual issue. As an instructor, my goals with this stage are to ensure students know how to use a broad range of library resources (including going into the stacks and finding actual books); understand what it takes to find, evaluate, and select a strong body of evidence; and experience the ups and downs of research for themselves, from the joys of serendipitous finds to the challenges of too-broad and too-narrow searches. - Telling that new story:

Drawing on the research they’ve done, the sources, images, and media they’ve gathered, and feedback from me and their class colleagues at various stages, students present their findings using Microsoft’s web-based Sway program. In each four-part presentation, they highlight their object’s museum, beyond-museum, and new stories, and they share their experience as researchers as well.

With their online Sway presentations complete, my COLL 100 students are ready to share the stories they’ve produced with each other and with many others, something a traditional in-class project rarely allows. Best of all, the narratives they’ve evaluated, researched, and constructed are reflective as well as analytical, and personal as well as scholarly. They’ve not only produced a good story; they’ve thought deeply about what that means and how and why it matters.

Spring 2021 Sample Student Projects:

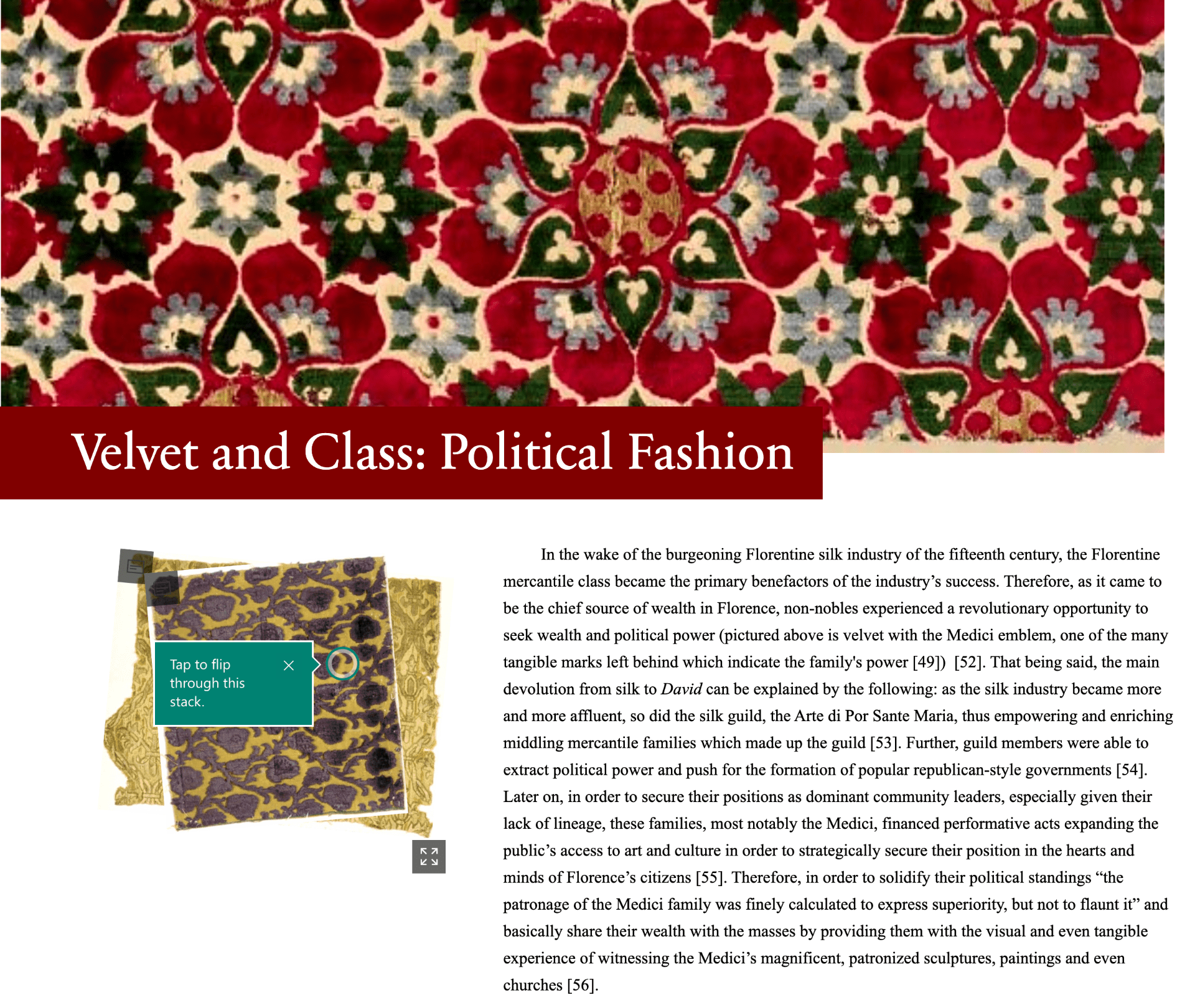

• Megan Bissonette, a velvet chair belonging to a counselor to King William II

• Charles Ciccoretti, the A7-L pressure suit worn by Neil Armstrong

© 2021 Laurie Koloski. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.

Meet the Author

Laurie Koloski

Associate Professor, History

Laurie Koloski teaches in the Department of History, where she’s a specialist in twentieth-century eastern Europe. She especially enjoys working with first-year students and teaching about the history of “stuff.”